At Synack we really enjoy great vulnerabilities, whether in web, mobile, host or even in completely outrageous devices and systems (satellite hacking anyone?). But we always keep the great findings that we and the SRT have made for our customers confidential. So while this won’t be a post about a great vuln in a Synack customer, it covers the exact type of thing that we see on a weekly or sometimes daily basis: A vulnerability in a system with millions of users that leads to a complete compromise of system security.

I recently found a vulnerability in Microsoft’s Live.com authentication system, which, if you have an account with any Microsoft service, probably would have affected you. This post describes the full details of the vulnerability now that Microsoft has patched the issue.

Introduction

The average person’s understanding of computer security has always been fairly limited. Back in the day, if someone heard that you were involved in computer security, the standard question would be “can you hack my Hotmail”, or more often, “can you hack my friend’s Hotmail”. I suppose that back in the day people still used Yahoo mail and Microsoft had yet to acquire Hotmail, but that’s a little bit too far back! Inevitably you would either suggest that the person just guess the person’s password reset questions, or install Sub7. Actually hacking Hotmail was bound to be too difficult, not to mention entirely illegal.

The information security world has changed a lot in the last couple of years, and unlike in years past, Microsoft now fully encourages security researchers to attempt to “hack Hotmail”. Of course Hotmail has been turned into Outlook.com, and these days everyone wants to know if you can hack their Facebook, but that’s beside the point.

The Microsoft Online Services bounty program was recently updated to include “Microsoft Account” as a target, which is basically the login systems hosted at each of these domains:

– login.windows.net

– login.microsoftonline.com

– login.live.com

In the above list, login.live.com is the authentication system that you will go through if you are attempting to authenticate to Outlook.com and a huge number of other Microsoft services. I decided to examine it first to see if I could discover any issues. As expected, the various API’s used to process a login appeared to be well hardened. Additional layers of protection existed in many places; for example, in some places passwords are encrypted with a public key before transmission despite all communications taking place over HTTPS.

After testing for a few hours, I discovered a few minor issues which I reported, but nothing really of note. When testing web applications I often find that the most common workflow is also the most secure, so I branched out to examining other ways that a user could authenticate to the live.com system. Almost a year ago I had found several OAuth vulnerabilities in Yammer which was also a Microsoft Online Services bounty target, so that’s where I looked next for live.com. This is where the interesting findings start!

Vulnerability Background

Before I get right into the vulnerability discovered, a quick overview of the misguided security system known as OAuth is necessary:

Wikipedia tells me that “OAuth provides client applications a ‘secure delegated access’ to server resources on behalf of a resource owner”. Wikipedia also has some scathing comments on its evolution and security, which are worth reading for a good laugh. Realistically, all OAuth does is allow a user to grant access to some or all of their account’s access to a third party. I made a MS Paint drawing to illustrate this because I couldn’t find a great one on Wikipedia.

As can be seen in the above image, you have a Server who the User authorized to give access to their account to a Client App. The mechanism that handles this behind the scenes can be built in several different ways, which are defined in the OAuth RFC. One way to build it is to an “implicit” authentication flow, which involves the authentication server giving an access key directly to the client. Another popular way is to use an “authorization code” procedure, where the authentication server gives out an authorization code, which the client system takes, and then exchanges for an access key using its client secret value. Microsoft has a good description of their usage of how they have implemented these mechanisms for live.com here:

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/hh243647.aspx

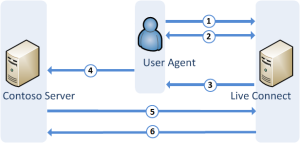

The graphic they made for the “authorization code” flow looks like this:

An image like that is great for understanding the process, but to me as a pen-tester also shows a lot of opportunities and places for things to go wrong. So with that as the background, on to what was discovered!

What Could Go Wrong?

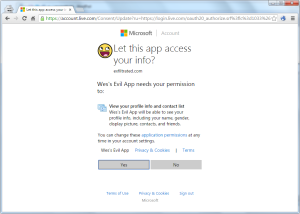

As noted in the above section, there are a lot of places that something could go wrong. One of the fundamental steps in the OAuth authentication procedure is for a user to choose to grant an application access. This is usually accomplished through a prompt like this:

Generally a user will only need accept this prompt once, but until they accept it, that app will not have any access to their account (whether or not the average user will permit Wes’s Evil App to gain access is perhaps a different question!).

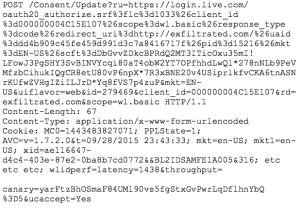

Thinking as an attacker, it would definitely be great if we could accept the request on behalf of the user. Unfortunately for me, the “X-Frame-Options” header was set to “deny” (x-frame-options settings were out of scope for this bounty too). So while clickjacking is out, I decided to get a better understanding of how the request itself worked. If a user clicks “Yes”, the following request is POST’ed to the server (plus some boring headers):

While the URL path above includes some generated tokens, testing showed that they were unnecessary for the request to succeed. A POST to the following URL would work just as well:

https://account.live.com/Consent/Update?ru=https://login.live.com/oauth20_authorize.srf%3flc%3d1033%26client_id%3d000000004C15E107% 26scope%3dwl.basic%26response_type%3dcode%26redirect_uri%3dhttp:// exfiltrated.com&client_id=000000004C15E107&rd=exfiltrated.com&scope=wl.basic

The cookie sent with the request needed to contain a valid session token in “IPT”. This cookie value is populated byhttps://login.live.com/oauth20_authorize.srf before the page prompting the user for permission is displayed. This happens regardless of whether or not a user ultimately clicks “Yes”, although it is set by some Javascript code, so if we’re attacking this process, we would have to force the user to load that page at some point.

If you’re following along, hopefully you’re now asking, “OK, so what about the POST request itself, and that canary value?”. I’d examined all the other parameters and communications flows first, as seeing a value labeled “canary” being sent with a POST request almost certainly means that it is being used as a token to prevent CSRF attacks. The point of security testing, however, is to verify that assumptions are indeed correct. So I modified the POST request, and changed the canary value to“hacks_go_here”. Instead of redirecting to a 500 error, the server sent back a positive response!

CSRF to PoC

Since the CSRF token was the last thing I’d tried to tamper with, I knew for certain that this should make for a valid CSRF vulnerability. As with almost every CSRF attack, the only prerequisite was that the victim was logged in, and had a valid session token in their cookie. Unlike many other web vulnerabilities, the impact of a CSRF vulnerability is entirely dependent on the affected API function. This CSRF lets me bypass the user interaction step of the OAuth authentication system, but a PoC is worth a thousand words, so the next step was to build some code to appropriately demo the impact of this vulnerability.

In the normal OAuth authentication flow, after the user grants access, the server should return an access code to the user. The user passes that to the client application, which can then use the granted permissions. A live.com client application can request a wide range of possible permissions. I considered just dumping the user’s contacts or something like that, but why sacrifice on the goal of hacking Hotmail now? The permissions my PoC needed then were:

wl.offline_access+wl.imap

Offline wasn’t all that necessary, but I threw it in to show that it would be granted.

With the necessary permissions chosen, there are 4 steps to gain access to a user’s email account:

1) We need to make an authorization request for our client app using the above permissions. The server will prompt the user to accept or refuse.

2) When a user accepts our request for those permissions, the server will append an “#access_token=<token>” parameter to the redirect that we instruct it to take.

3) Since our server side scripts will need access to that value, we need to make a simple page to take the token from the browser URL field and pass it to our server.

4) Finally we need some scripts server side to take that token, and use it to log in to IMAP. Microsoft has a somewhat convoluted process for using the OAuth token to log in directly via IMAP. A few sample libraries do exist for this, and the whole process is described on this page:

https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dn440163.aspx

That workflow would work fine assuming the user chooses to give us permission. I now just need to modify the workflow to instead include the CSRF. As noted earlier, the live.com authentication server will be expecting a session token in the IPT cookie. We can ensure that is populated by first sending the user to a validhttps://login.live.com/oauth20_authorize.srf page. Immediately after, we can execute the CSRF request which will make use of the newly populated cookie value. This can now replace step 1 and force the server to immediately jump to step 2.

Demo and Impact

Microsoft has now fixed this issue, but here’s a quick video showing it in action.

As can be seen in the video, all that is really necessary is to get the victim to visit your malicious webpage. The demo wasn’t designed to be sneaky and run in the background of a website, or as part of some malicious banner ad, but it certainly could have been made that way.

Using this as a targeted attack definitely has a high impact, but this is also the perfect type of vulnerability to turn into a worm. With IMAP and contact book access, a worm could easily email all of a user’s contacts (or at least the ones who use Hotmail, Outlook.com, etc), with something enticing, “ILOVEYOU” virus style, and spread to every user who clicks the link.

Final Thoughts and Timeline

Hunting for this vulnerability and making a working PoC involved a fair amount of effort digging through the various live.com API’s. Looking back at it all however, this really is just a classic CSRF vulnerability. The only thing that’s surprising about it is that it’s in a critical authentication system which ultimately can be used to take over any user’s account.

As an outside tester I have no idea how long this vulnerability may have existed, or if anyone ever tried to exploit it. At the same time, it is findings like this that definitely show the value of allowing outside testers to submit vulnerabilities to your company before attackers leverage them against you. Microsoft is far ahead of most companies when it comes to security, and yet are still suceptible to issues like this one. Synack’s experience has been that vulnerabilities are uncovered even in seemingly well secured systems when a large group of outside researchers test that system. That is essentially the premise that Synack operates on, and is why more and more companies are offering their own bounty programs (I, of course, would recommend Synack’s program over running your own!).

As can be seen in the timeline below, Microsoft was responsive in getting a fix for this issue out, which was great to see.

Timeline:

August 23, 2015: Vulnerability discovered

August 25, 2015: Vulnerability reported to Microsoft

August 31, 2015: Microsoft issues case number for vulnerability

September 15, 2015: Microsoft releases fix for issue, issues $24,000 bounty (double bounties promo)